conceptual inquiry regarding meaning

The theory addresses how the implicit concerns of our everyday lives (from tab 0) are best translated into explicit questions. This will involve the articulation of those questions, which will itself involve using langauge to articulate them. It must be kept in mind that any articulate language we use to explicitly inquire about experience will be as a map to terrain and will never fully capture that terrain. A language is in part a set of terms together with rules defining how those terms are to be related to each other, all of which point to experience beyond words. Our theory is thus a theory about how articuale language relates to unsaid experience, what terms are, and how those terms relate to each other.

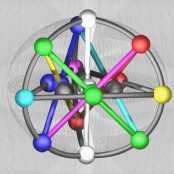

Overall, the Project is hermeneutic in nature, so its logic is formally circular, but it's circular in an open-ended way—ever open to reinterpretation when applied to actual experiences. The terms in which the questions are asked are formal indications. It's concepts point toward actual experiences, and, taken together, the system of concepts point "around" a central mystery, the wonder of existence. So, taken together, the terms in which this Project's questions are asked bear no conceptual content. The system of formal indications is self-cancelling. The idea is to build a formal structure around our central question without getting in its way. We can't understand the meaning of existence conceptually, but we can understand "around" it. The formal structure will thus ideally be as a conduit through which the light of wonder/mystery may illuminate the lives of the Project's participants.

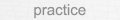

The Project is in dialogue with itself. Its parts are open questions, and each is asked in the context of them all—the whole. (See the image to the left.) These are questions that we as humans tacitly answer on an ongoing basis, even though the questions themselves are rarely explicitly asked. For example, this Project's central question can be asked, what does it mean to exist? We ask this on an ongoing basis because we care about our own existence, and we continuously answer given the way we live our lives and experience existence.

The Project is in dialogue with itself. Its parts are open questions, and each is asked in the context of them all—the whole. (See the image to the left.) These are questions that we as humans tacitly answer on an ongoing basis, even though the questions themselves are rarely explicitly asked. For example, this Project's central question can be asked, what does it mean to exist? We ask this on an ongoing basis because we care about our own existence, and we continuously answer given the way we live our lives and experience existence.

On the one hand, the question what does it mean to exist? is so broad that it encompasses all questions relevant to our lives. On the other hand, the question isn't a single, all-encompassing question, but a potentially infinite number of questions asked and answered in a potentially infinite number of ways. It's asked any time we encounter an issue in our lives, and it's answered as we resolve the issue and continue on our way in a particular way. So, again, even the meaning of the central question about meaning comes from its reference to the totality of issues we address in the course of our lives.

Of course, we couldn't possibly live our lives if we were to stop and explicitly ask ourselves every relevant question that implicitly comes up. Mostly we have a prescripted set of general answers. And for the most fundamental questions, our prescripted answers come mostly from our culture. Yet it is helpful to check in from time to time, thinking critically about the prescripted answers we live, staying consciously in touch with our meaning, and reinterpreting that meaning by living differently when it's helpful or healthy to make a change.

Now, the question what does it mean to exist? can apply to human beings, but it can also apply to anything else that can be said to exist. What does it mean for anything to exist? —or, what is the meaning of existence as such? That's an open question insofar as it's relevant to our experience, and to expand it therebeyond, we have to stay in touch with its relevance to us. So, while this Project's questions aren't limited to the domain of humanity, it's in this domain that we must start. Indeed, mostly participants will start at a more particular domain than humanity; we'll start at the level of our culture (whatever culture that may be). Either way, it's relevance that we need to keep hold of; otherwise the questions risk wandering away to meaninglessness.

Looking closer, the questions foregrounded by this Project as its parts precipitate together (as a set) out of the whole of our experience, given basic patterns in the types of issues juggled in the course of living life. Yet before the questions appear to conscious reflection, they're all mixed together. For example, we don't at one moment in our lives implicity ask what is the nature of reality? and in another how does one live a good life? For sure, they can be foregrounded at different times, but once they have ever been explicitly asked, both always remain open questions mixed together in our background. Most people are fortunate enough to have reliably working answers for these questions, and so they don't often come up, but they're always there, and we answer them tacitly given the way we live our lives.

When we do foreground one or another of these questions, we must remember that they originate from a condition of being mixed together in our ever-present background. So, to adequately understand any of these questions individually, each must be kept in dialogue with the others. Otherwise, again, they might lose their connection with relevance and wander away to meaninglessness. This Project keeps its questions in dialogue by encouraging participants to raise each with reference to each of the others. For example, we might ask how does what I believe about the nature of reality condition my conception of a worthwhile life? or how does what I value condition what I'm willing to accept as true? or how does my embodiment condition my beliefs about who I am? and so on.

Again, each of this Project's 26 core questions can (and should) be asked with reference to each of the others. This means we'll need to ask each question in 26 slightly different ways. But beyond that, these questions are multi-layered. Only the tip of the iceberg—a general understandng of each question—is presented in this introductory presentation. Beneath the tip is the layer where each question is asked in 26 slightly different ways. Beneath that are a potentially infinite number of additional layers, each integrating the questions to a more finely-grained degree, approaching the continuity of our analogue actual experience (where the questions are completely mixed together). The internal dialogue generates a fractal pattern, and we live at the level at which these questions approach infinity at our horizon.

Since we can't get outside existence/experience, working out its meaning can't be a matter of standing apart from and characterizing it as we might an object of reflection. We have to work out the meaning from within, interpretively. This Project therefore adopts an hermeneutic (interpretive) approach to its core questions.

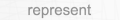

The image to the right diagrams the general features of this method: We encounter something (in this case, an issue/question) in our foreground (a), and on the basis of our background (f)—i.e., our familiarity with the world—we project (b) an array of possibilities (c) regarding how we might understand what we're encountering. We then pursue those possibilities, actively engaging (d) with the world, aiming to find which possible understanding works best given the situation. This purposive engagement brings us knowledge and experience, updating (e) our background (f). This updated background changes (g) the way we're attuned/disposed (h) to the world such that, as we reapproach (i) our foreground (a), we encounter it differently.

This hermeneutic approach is employed in four different ways as for each of the Project's 26 core questions we ask:

Each of these questions presupposes an hermeneutic dialogue between part and whole, foreground and background, and/or text and context. Also, the methods aren't mutually exclusive; the questions above will overlap.

The structure of the Project's methods of interpretive inquiry mirrors the structure of the Project's core questions. Questions regarding how questions are concretely delimited relate to the L-phase. Questions regarding a question's practical significance relate to the A-phase. Questions regarding a question's transformative power relate to the O-phase. And questions regarding a question's formal character relate to the I-phase.

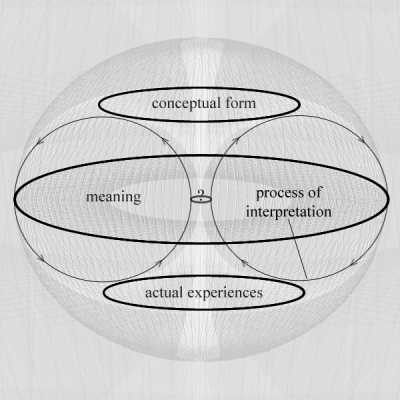

This Project's terms are formal indications. "[F]ormal indication is a use of signs the content of which is indeterminate, but that comprises a constraint serving to bring about the state of understanding from which they arise. In this sense, formal indications are to function as a pointer, a signpost, or a path 'back' to the corresponding grounding experience" (Inkpin [2016] pg. 77). Conceptual form, abstracted from experience, is itself empty but "shaped" in such a way that it can only point to the set of actual experiences that will "fit" into (fulfill) it. Project participants will provide the actual experiences; so, what the Project's terms mean to each participant will vary slightly. Also, the terms are not to be confused with answers to the Project's questions. Answers are meant to present themselves experientially; they're meant to be lived. Terms are tools to help us make that happen.

A formal indication is a type of mental representation pointing "back" (down, in my diagram) at the experiences upon which understanding is actually grounded. "[P]ut simply, 'formal' or 'empty' signification and actualized or performed understanding are two extremes between which interpretation mediates" (Ibid. 78). The diagram to the left—with the matching extremes of conceptual form and the actual experiences indicated—is meant to be understood as dynamic. As actual experiences constantly change, the form into which experiences will "fit" correspondingly changes. Ideas and experiences are in dialogue, and it's through this dialogue that the meaning of a formal indication is to be interpretively found, as grounded in actual experience. This Project's terms are therefore fundamentally flexible. "[F]ormal indication is a use of signs through which phenomena are addressed in a provisional, tentative, and hence corrigible manner. Understanding the functioning of signs in this way means that phenomenological inquiry can be understood as an ongoing cycle of interpreting phenomena—with signs formally indicating phenomena and phenomena prefiguring the forms of symbolic indication" (Ibid. 79). This Project's terms will, therefore, always be somewhat blurry as if moving. Indeed, the terms aren't distinct and static, but overlapping and dynamic.

A formal indication is a type of mental representation pointing "back" (down, in my diagram) at the experiences upon which understanding is actually grounded. "[P]ut simply, 'formal' or 'empty' signification and actualized or performed understanding are two extremes between which interpretation mediates" (Ibid. 78). The diagram to the left—with the matching extremes of conceptual form and the actual experiences indicated—is meant to be understood as dynamic. As actual experiences constantly change, the form into which experiences will "fit" correspondingly changes. Ideas and experiences are in dialogue, and it's through this dialogue that the meaning of a formal indication is to be interpretively found, as grounded in actual experience. This Project's terms are therefore fundamentally flexible. "[F]ormal indication is a use of signs through which phenomena are addressed in a provisional, tentative, and hence corrigible manner. Understanding the functioning of signs in this way means that phenomenological inquiry can be understood as an ongoing cycle of interpreting phenomena—with signs formally indicating phenomena and phenomena prefiguring the forms of symbolic indication" (Ibid. 79). This Project's terms will, therefore, always be somewhat blurry as if moving. Indeed, the terms aren't distinct and static, but overlapping and dynamic.

Let's try this with an example. We start with a question (and, for simplicity's sake, let's say the question is explicitly asked). Let's take the question, what is a self? Insofar as the questioner is able to pose the question in the first place, she already has some vague notion of what she's asking about. Self already means something to her, based on her background. This meaning will be some vague mixture of ideas and actual experiences from her past. Now, having asked, she projects a range of possible definitions. These projections are ideal abstractions from the way the fuzzy concept of self already means something to her. As abstractions, they're ideal projections. They're concepts—ideas—but ideas of what? Ideas are only meaningful in a non-trivial way when they refer to actual experiences. So, while projecting ideas, she must try to recall when she actually experienced something she would identify as her self. Her ideas must refer to those actual experiences. Of course, an experience of one's essential self is hard to come by, so this will not be an easy task. She'll have to interpret her actual experiences in light of her ideas just as she has to interpret her ideas in light of her experiences. Through this interpretive dialogue, she can home-in on what she means by self.

Of course, actual experiences of one's self, or anything else, will come mixed together with actual experiences of other things we might ask about. Likewise, any projected idea will be projected in the context of countless other ideas we've projected. And, naturally, whenever we make sense of anything—when things have meaning—that meaning comes in the context of how we're making sense of anything. So, none of the three horizons pictured in my diagram above exist independently of other horizons relevant to other questions.

Returning now to the notion of formal indication. Again, this notion pertains to ideal projections representing actual experiences. It pertains to the horizon of conceptualizations. Formal indications refer to actual experiences (vertically, in my diagram), but they also refer to each other (laterally) in theories involving multiple conceptions. In this Project, the form that a formal indication takes is determined by the combination of, on the one hand, how it helps one re-experience the actual experience it indicates and, on the other, how it relates to the forms of other concepts in theories. So what I mean by conceptual form is the way concepts relate to each other in theories, irrespective of the phenomena they refer to (except insofar as complete theories are themselves abstracted from experience). The forms of particular terms (and their definitions) can be thought of as pieces in puzzles. The pieces are the conceptual forms that together form theories. It's important that the shapes of the pieces are such that they fit together with no gaps, giving an overall account of the phenomena a theory refers to.

Now, usually a theory is meant to apply to a particular set of phenomena and not other sets. Usually theories describe an horizon within a broader horizon, as particular regions within a larger whole. We can extend the puzzle analogy and talk about puzzles the pieces of which aren't just concepts in theories, but theories themselves, such that the theories themselves have form and fit together with other theories. But the concepts in this Project are meant to work together to give an account of experience as such—not a particular region of experience. Because of this, when the pieces fit together, the whole mustn't have a form of its own. There's nothing in particular for its form to fit together with. So, as a whole, this Project must remain conceptually without form.

And what does it mean for the Project to remain without form? It means that, with respect to the conceptual forms of its terms, the terms are interrelatedly defined in such a way that, taken together, their forms self-cancel. Their relational logic is circular—the cirlce of a snake swallowing its own tail.

To illustrate this, let's take the basic most terms involved in this Project. The Project's central question asks about the meaning of experience as such—not a particular experience, but experience as experience. What is experience as such? Well, it seems to be what occurs when an experiencer experiences that which is experienced. And when the experience is just experience as such and not a particular experience, the experiencer is an experiencer as such (no particular experiencer), and so on for the other two. But experiencer as experiencer (and nothing more) is what it is only with respect to its relations with experiencing as experiencing (and nothing more) and experienced as experienced (and nothing more). The three constitutive terms invovled in this formal definition of experience as such are interrelatedly defined. At this level of abstraction, when separate they're utterly meaningless (even formally). Each has meaning—albeit mere formal meaning—only in relation to each of the other two. And together they formally self-cancel to indicate the phenomenon of formless experience as such—the experience of nothing in particular. In sum, if our formal indications are to together point at an experience of nothing in particular, their form together must be no form in particular. They must together be without form.

At this level of abstraction, conceptual forms are like math. Take this analogy: experiencer is to -1 as experiencing is to the operation of addition as experienced is to 1. Together they equal 0. They self-negate.

To this end, this Project's terms are appended to a structure called l'arbre de rien—French for the tree of nothing (the 3D image shown below under "logic map"). The tree with its 21 nodes appears in 4 phases. The vertical axis (I-phase) unfolds along the arcs (O-phase) to become the spectral array of segments (A-phase) before flattening at the horizon (L-phase), or vice versa. The phases and nodes are assigned letters such that each may be easily referred to.

The self-cancelling nature of this Project's terms simultaneously 1) keeps the Project in dialogue with mystery, 2) keeps its terms transparent, such that they don't get in the way, obstructing actual experience, 3) provides a way to articulate the meaning of experience as such—or, at least aspects thereof—and 4) prevents the idolatry of naming or characterizing the totality.

Once again, it's not the meanings of the Project's terms that self-cancel into meaninglessness/nonsense. It's not the meanings of the terms that swallow up their own tail. Meanings present themselves through the process of interpretation, where ideas are placed in dialogue with actual experiences. What self-cancels is the mere ideas involved in the terms—that is, the pure ideas as empty indicators (unfulfilled formal indications). Ideas are just tools that help us navigate our experiential lives. Actual experiences serve as ground for meaning. Actual experiences together form our terrain, while ideas make up its map. We don't want the map to get in the way of the terrain. Nor do we want to idolize, reify, or deify the map. Once we've mastered the terrain, the puzzle the map's pieces have put together for us forms a transparent image, and we go explore new lands. It's the actual explorations that count as answers to the Project's questions.

This Project's four phases constitute different ways to approach the question of meaning. I addresses the transcendental conditions making experience possible, which amounts to how we can conceptually make sense of the fact that experience occurs. O addresses the experiential dimension of the question, looking at the different ways experience occurs as intelligible. A looks at the practical nature of experience—how a meaningful space is opened given the purposive activities we're performing—as if it's our purposive activities that breathe life (meaning) into an otherwise meaningless existence. L addresses the concrete conditions that make experience possible. The four phases overlap. They have a set of common terms (T, S, Y, Q, U, Z, R, X, and V), even if each phase interprets the terms differently. Click I, O, A, or L below to view how the phases overlap and how the common set of terms is differently interpreted.